Fort Norfolk History - 1862

When the iron-clad Virginia (Merrimac) was ready for service it as found that she lacked thirty-one men of having a full crew, and Captain Kevill was applied to for volunteers to make up the deficiency, but the men were not willing to serve under the command of the naval officers and declined to volunteer unless one of their own officers was on board the ship to take charge of them. This was reported to the Secretary of war and by him communicated to the Secretary of the Navy, and the result was that the services of the company were accepted, with Captain Kevill as their commander. The Captain then called for thirty-one volunteers, And the whole company stepped to the front. Selecting Thirty-one men whom he thought best qualified, by physical strength, to do the heavy work which was required of them, he reported to the Commandant of the Navy Yard on the 7th of March, 1862, and was assigned, with sixteen men, to one of the 9-inch broadside guns. During the engagement the fifteen other men were distributed among guns which were short in their crews. During the second day’s engagement, the 9th of March, a piece of metal was knocked off the muzzle of the gun, but the men continued to load and fire it until the close of the battle. The next time the ship went down to Hampton Roads Captain Kevill was again with his men, but on the third trip, May 10th, Lieutenant Lakin had command of the detachment. Two men belonging to the company, A. J. Dalton and John Capps, were wounded by musket balls coming through the port holes in the first day's battle, March 8th.

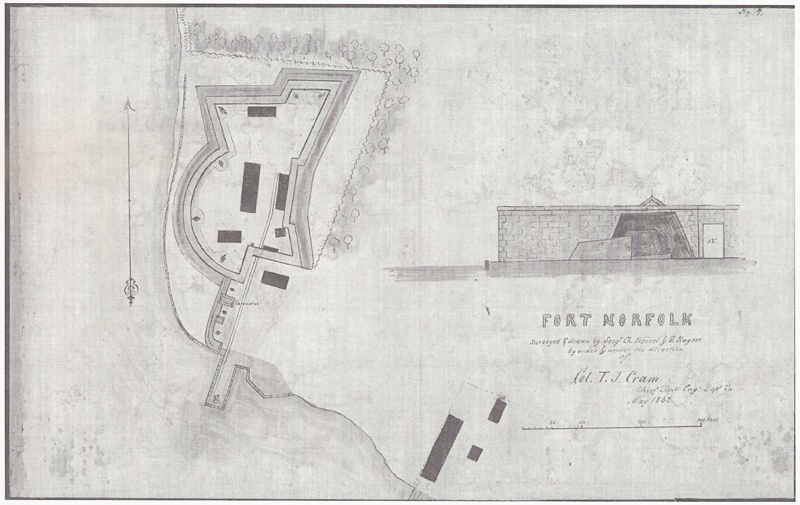

On the 10th of May 1862, before sunrise, the company was marched from Fort Norfolk to the entrenched camp and placed in charge of a battery of heavy guns, and remained there until early in the afternoon, when it was marched to the Norfolk and Petersburg railroad depot in Norfolk and took the cars for Petersburg.

In May 1862, Union forces took the City of Norfolk. Retreating Confederates destroyed several naval properties and facilities, but Fort Norfolk survived structural damage as did the Randall & Brown warehouse. The Confederates did manage to spike the guns at Fort Norfolk before leaving.

Fort Norfolk was not returned to the U.S. Navy as an ammunition storage facility. On May 22,1862 Major-General John E. Wool wrote Naval Flag-Officer L. M. Goldsborough and Secretary of War Stanton "I would remark that Fort Norfolk was surrendered to the troops under my command on the 19th instant by the rebels at Norfolk. I cannot, therefore, permit the Navy to take possession of it without an order from the President of the United States or the Secretary of War."

On August 7, 1862 Brigadier- General E. L. Viele wrote to Major-General Dix "I have at Fort Norfolk accommodations for 100 prisoners. In a day or two will be ready for 200. There is now one company on guard there." Fort Norfolk would become a prison camp for most of the war.

The Randall & Brown warehouse was briefly pressed into service as a naval hospital. The frequent assertion that Fort Norfolk itself was used as a naval hospital during the Union occupation of Norfolk is incorrect. Nonetheless, it has made its way into the historical literature (see for example U.S. Army Engineer District, Norfolk n.d.:3). In 1862, Augustine Morrell filed suit against the U.S. Government to recover rent as well as compensation for equipment and chemicals stolen from his warehouse and damages to the wharves. The "historical error" probably resulted from the fact that the Randall & Brown lot was referred to rather confusingly as being "at Fort Norfolk" in the post-war proceedings held by the Federal Claims Commission. In May 1862, Augustine Morrell applied to have his warehouse and land returned by the military governor of Norfolk. His request was denied. Morrell later testified that the fleet surgeon of the blockading squadron at Norfolk ordered the warehouse to be "cleansed, repaired, and fitted up." From June 26 through September 6, 1862, the Randall & Brown warehouse served as a naval hospital. On the latter date, the U.S. Army took over the grounds despite Morrell's protests. Morrell stated that his property remained "substantially under the control of the Quartermaster Department until the 31st of October 1865 and was used for quartering troops and contrabands and for storage purposes" (OQMG Claims Commission brief, May 29, 1867).

More History

Back, 1673, 1775, 1787, 1789, Army before 1793, 1793, 1794, More 1794, First Fort, 1795, 1796-1800, 1801-1806, 1807, 1808-1811, 1812, 1813, 1813-1814, 1816, 1817-1818, 1820-1821, 1824, 1835, 1842-1844, 1845, 1849, 1851, 1852, 1853, 1854, 1854 Keeper's House, 1854 Changes, 1858, 1859, 1861, 1862, 1863, 1864, 1875, 1884, 1893, 1903, 1923, Next

Source of Information

A CULTURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN OF FORT NORFOLK, NORFOLK, VIRGINIA prepared for U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk District by the College Of WILLIAM & MARY, November 1995 under Contract No. DACW65-94-Q-0075.

RECORD OF EVENTS IN NORFOLK COUNTY, VIRGINIA, FROM APRIL 19th, 1861 T0 MAY l0th,1862, WITH A HISTORY OF THE SOLDIERS AND SAILORS OF NORFOLK COUNTY, NORFOLK CITY AND PORTSMOUTH WHO SERVED IN THE CONFEDERATE ARMY OR NAVY. BY JOHN W. H. PORTER 1892

David A. Clary's Fortress America: The Corps of Engineers, Hampton Roads, and United States Coastal Defense (1990)

William Bradshaw and Julian Tompkins's Fort Norfolk, Then and Now (n.d.).

The Norfolk Public Library vertical file of recent newspaper articles on Fort Norfolk. Including articles by James Melchor of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers that describe archaeological and architectural findings on the fort property.